This text has been updated since our print copy was mailed. We have corrected a quote from Rosie Nevins-Alderfer which misrepresented her language. Despite having intentional conversations around changing language patterns away from harmful labels like “addict” the intrenched language habits were used. We have updated the quotation to accurately reflect Rosie’s wording and we are taking this learning opportunity to our broader audience. We encourage everyone to take time and care in reflection on the words we use.

As the recipient of this Newsletter, you most likely already have an established relationship with the Housing Trust and the important work we do, and therefore know that our mission often intersects with our society’s most pressing issues. The opioid epidemic is arguably the most devastating public health crisis that our country has ever faced, and it is hitting Vermont especially hard. It is staggering in scope, and the human toll can be felt in every corner of every community, across the entire socio-economic spectrum. In this article, we explore Vermont’s opioid epidemic, and introduce you to some amazing folks on the front line of Windham County’s progressive response. It’s a big topic, that impacts each of us; it’s also constantly evolving. But by keeping an open mind and an open dialogue, we are finding the path forward and taking a role in combating this community health crisis – but it’s not one that any one agency can tackle alone, this requires a community-wide, state-wide strategy.

Before the pandemic, it looked like progress was finally being made in addressing the opioid epidemic in Vermont. The medical community had tightened its prescription rules and new, effective treatments, like medication-assisted treatment (MAT), were becoming more widely available. Supportive Housing Communities – like Great River Terrace – were connecting people with services, resources and hope. Then COVID-19 struck and all the external stressors lead to a sharp increase in use.

More than 100,000 people in the United States fatally overdosed on drugs during the first year of the pandemic – the highest number ever recorded. Sadly, Vermont experienced one of the steepest climbs in overdose deaths among all states during this time – 181 Vermonters died from overdose in 2021, up from 158 the prior year. These numbers are breathtaking, but they don’t tell the whole story. They don’t tell the human story. Behind each statistic, there is someone’s child, or parent, or husband or wife, and an entire family torn apart from losing a loved one. And there is always a backstory – one that often includes emotional trauma, mental health struggles, poverty, discrimination.

How did we get here? How did things get so bad? Rosie Nevins-Alderfer and Jedediah Popp are co-directors of the Windham County Consortium on Substance Use (COSU). They claim that, although COVID played a role, the data reveals this is not just a pandemic problem.

ROSIE: “Since 2000, the number of people being treated for Substance Use Disorder in the State has escalated by 1,500%. Fatal overdoses have been on the rise for the past 10 years, driven largely by fentanyl, which is 100 times more potent than heroin. Currently, 1 out of every 12 Vermonters is living with some form of SUD.”

COSU launched in 2019 as a community-driven, collaborative effort to address the opioid crisis and SUD in Windham County. The organization works across the span of prevention, harm reduction, treatment and recovery to identify and fund projects that respond to the impacts of SUD, and the underlying social determinants that contribute to its cause.

ROSIE: “At the heart of our work is a shift of focus back onto the needs of people who are living with substance use, and meeting them where they are at. We value people with lived experience, and ask them to be the wisdom holders.”

Meeting people where they are at often means doing everything possible to keep someone alive. It’s an essential step in a complicated path to recovery.

ROSIE: “For me, grassroots harm reduction is not just about keeping people safe and alive until they are able or ready to access treatment—though certainly it is a critical component of many people’s recovery journey. But at the heart, it is about basic healthcare for people who use drugs regardless of whether they ever want or need to access treatment for SUD. It’s about respecting people’s autonomy and dignity by meeting people’s basic needs without any strings attached.

Jedediah is one of those folks with lived experience. Following many years of opiate use, Popp was homeless when they arrived in Brattleboro in 2012 and would remain so for close to a year. During their history with substance use, Popp had multiple incidences where Narcan was administered due to overdose. They credit interventions like this, as well as support from the Brattleboro community and the relationships they developed with saving their life and helping them to recover from substance use issues and get back on their feet.

JEDEDIAH: “It takes an entire community to assist somebody out of active use and into recovery. At COSU, so much of what we do and what our efforts are geared towards is harm reduction – as well as prevention, treatment and recovery. Those basic principles, meeting people where they are at, treating them with dignity and respect, and making sure they have their basic needs met – it’s so very important.”

Top on the list of those basic needs – is housing. Josh Davis is the Executive Director of Groundworks Collaborative, the organization that provides supportive services to populations experiencing substance use and homelessness. Over and over, he has seen the link between housing and recovery.

JOSH: “Housing is connection. Services are connection. Permanent supportive housing for people who need it most, is connection. It’s hard to think about people being successful without having the stability of a place to live. Just think about some of the things we take for granted when we have housing. An address. Electricity. Food in the refrigerator. Safety – the ability to shut and lock the door at the end of the day. The housing piece is huge in providing stability, and the opportunity for connection with service providers, but also connection with the community.”

The importance of that connection became crystal clear, says Josh, during the first 12 months of COVID.

JOSH: “We really saw the impact of housing when we became heavily involved in the emergency housing program. While we experienced an increase in overall substance use, our ability to make those critical connections with people who were housed at the Quality Inn, and offer harm reduction strategies on-site, actually reduced the number of lethal overdoses, when the numbers were rising elsewhere. Having access to our staff at Groundworks who were looking out for people and checking in with folks, that made all the difference.”

JEDEDIAH: “Housing can be the difference between life and death, especially supportive housing, that has a good working knowledge of harm reduction. Before COVID, I was doing some recovery groups at Great River Terrace – that community was so beautiful to see. Neighbors were helping each other out, basic needs being met. Substance use is the tip of the iceberg – so much contributes to that use. Trauma, poverty, oppression, discrimination – we can’t talk about substance use without talking about all of these other things. Knowing there is past trauma that a lot of people carry around, that takes a lot of work to get through. I know that, and I access white male privilege. People from marginalized communities have a much harder time accessing services. I’m always thinking about that.”

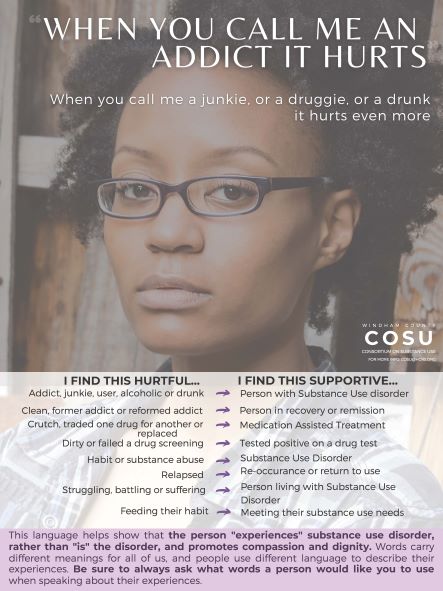

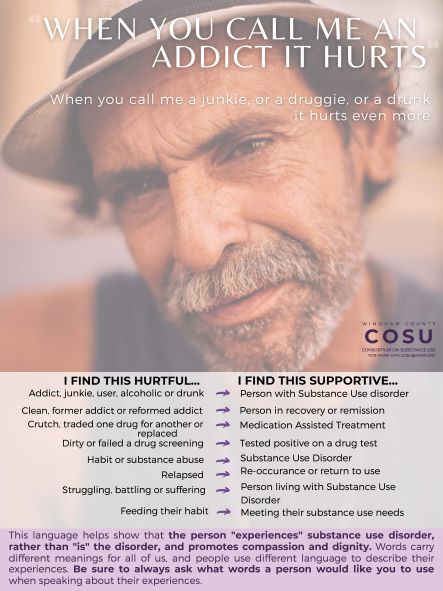

For those in the community who ask, what can I do? The answer is simple: create opportunities for connection rather than isolation and fear. Recognize the human behind their use. Become a strong advocate in the community for housing, a critical strategy for keeping those struggling with SUD safe and alive at the very least, and on the road to recovery. Polly Morris with WWHT Resident Services and Rosie and Jedediah offer some best practices.

POLLY: “Change the language you use when referring to people with an addiction. When we use person -first language such as, “person with an addiction”, we reduce the discrimination of stigma that blames people for a medical condition. When we speak differently about people with addiction, we change the way, we think, feel and act towards people with addiction. Communicate that people with addition are a part of the solution. Also, carry naloxone. This is an opioid reversal drug that can save someone from dying.”

ROSIE: “The number-one thing I’ve learned – people need to work on their fear. There is so much fear around substance use. Instead, if people could let go of that fear, and were open to educating themselves, that would open up so many other possibilities.”

JEDEDIAH: “Be open to learning. Authentically listen to people living with Substance Use – valuing what they have to say.”

JEDEDIAH: “It’s also important to recognize that there is a diversity of experiences – we can’t lump everyone with lived experience in together. Someone who is 20 years into their recovery will have a different experience than someone with a month or two. We need to talk to people who are active in their use right now. We need to listen to those folks – they have the most to offer.”

ROSIE: “Many people say that the opposite of addiction is not sobriety, it is connection — and connection occurs when we see each other as human — when we take responsibility for harm and pain — and are bold in our actions to offer each other support, and hold each other accountable for compassion, safety, and dignity.”

COSU is an organized, collaborative body, consisting of community members, members from partner organizations and people who are most impacted by substance use and overdose death. Funded projects center on the topics of Harm Reduction, Trading Discrimination for Dignity, Restorative Justice, and Social Determinants of Health.